Every time sheep are treated with an anthelmintic, the worms inside that sheep are exposed to the active ingredient within the product, putting selection pressure on that worm population. This is because genetically susceptible worms are killed, leaving behind worms with the genetic capability to survive exposure. These survivors then go on to breed and the proportion of resistant worms increases over the generations.

In time, the population will become totally resistant – which is why it is important to actively preserve susceptible worms, known as an in refugia population. Increasing the size of the in refugia (susceptible) population so resistant genetics can be diluted in the worm population is a key concept in delaying the development of anthelmintic resistance.

Preserving susceptible worms involves both managing the pasture and choosing which animals to treat.

Before anthelmintic resistance was as well understood as it is now, the recommendation to maximise the cost of a wormer was to deworm sheep and immediately move them onto a low contamination (clean) pasture. This dose-and-move approach selected heavily for anthelmintic resistance, as any worms surviving treatment would likely be resistant and enjoy an extended period of reproductive advantage over susceptible (unselected) worms, during which time the resistant worms would contaminate pasture with their eggs. When repeated over time, dose-and-move results in highly resistant populations of parasites. Therefore, SCOPS recommends two alternative approaches:-

It is worth noting that sheep treated with moxidectin will not become reinfected with susceptible teladorsagia or haemonchus for five weeks after dosing (longer for the long-acting 2% LA product), which means neither of these methods usefully reduce selection pressure on 3-MLs (clear) products in those worm species. Selective treatments (see below) are the option of choice where moxidectin is used, though a move and then dose strategy is an alternative.

Watch this AHDB 'Why not to dose and move sheep' video.

Leaving some animals in the flock untreated allows a pool of unexposed parasites to produce worm eggs to pass out onto the pasture the sheep are moved onto. As a rule of thumb, leaving about 10% of the flock untreated can delay the development of anthelmintic resistance, but this depends on farm conditions, the flock itself and the resident parasite population. It is good to start with a proportion of sheep you are comfortable to leave untreated and increase this number as you gain in confidence.

There is already practical advice on not blanket treating ewes at tupping and lambing time, and science to back this up. Find out more at www.scops.org.uk/internal-parasites/worms/treating-adult-sheep.

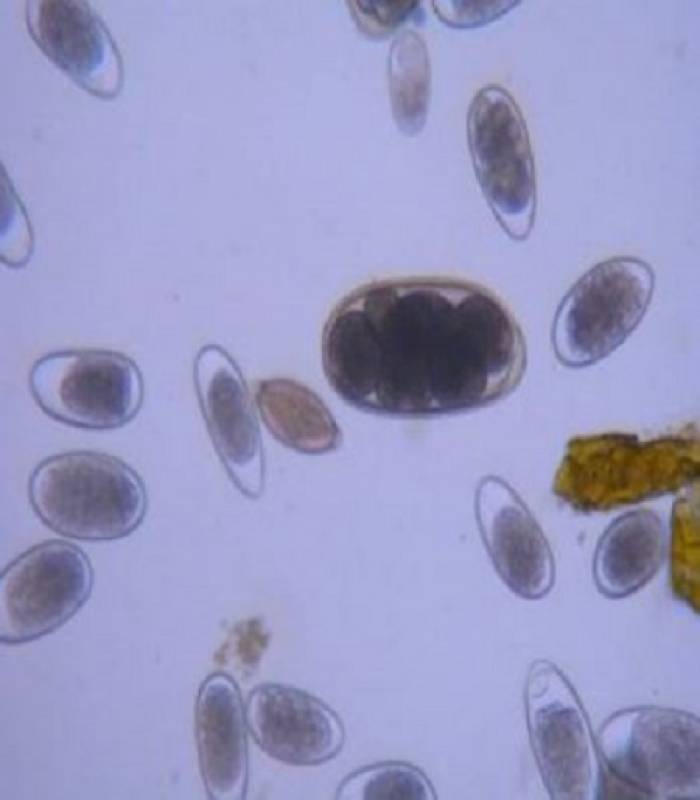

Targeted selective treatment (TST) is the gold standard for identifying sheep to safely leave untreated – be that because they’re resilient (thriving despite having a worm burden) or resistant (have a low worm burden). TST uses markers/indicators to select for the sheep that can be left untreated, such as growth rate and other production measures, dag/breech scores, faecal egg counts (FECs) etc. SCOPS is optimistic that continued development of TST approaches will make it accessible for an increasing number of sheep flocks. It is hoped more reliable and cost/time effective markers will not only make it easier for more flocks to adopt TST, but also help reduce scepticism that leaving some animals untreated and/or not maintaining clean pastures will not negatively affect production.

For vets/advisers there is more information on preserving susceptible worms in the SCOPS Technical Manual. Chapter 2.2.